Using the onboard CPX sensors

We’re going to expand our understanding of the CPX this week. Update your version of CircuitPython, and let’s roll.

We’ve already played with the onboard OUTPUT (lights, sounds). Now, let’s talk a little about input. If you missed our in-person lab session want a full guided tour with great photos, or just need a refresher, visit the Adafruit website. We’ll start by coding the buttons and slide switch so that you can control your device. Open Mu, load code.py, clear the code, and replace it with this:

import time

import board

import neopixel

import digitalio

pixels = neopixel.NeoPixel(board.NEOPIXEL, 10, brightness=0.3)

button_A = digitalio.DigitalInOut(board.BUTTON_A)

button_A.switch_to_input(pull=digitalio.Pull.DOWN)

#Colors

RED = (255, 0, 0)

YELLOW = (255, 255, 0)

GREEN = (0, 255, 0)

CYAN = (0, 255, 255)

BLUE = (0, 0, 255)

MAGENTA = (255, 0, 255)

WHITE = (255, 255, 255)

LIGHTSOUT = (0, 0, 0)

while True:

if button_A.value:

pixels.fill(CYAN)

else:

pixels.fill(LIGHTSOUT)

time.sleep(0.01)Click SAVE to load it and- nothing! It’s a button activated code, so press button A and – boom, Cyan lights. To add a second button, we clone the Button A code object and modify it a bit, like so:

button_B = digitalio.DigitalInOut(board.BUTTON_B)

button_B.switch_to_input(pull=digitalio.Pull.DOWN)Add that to setup. Then, we add an else if (elif) line in the loop to check to see if that button is pressed:

while True:

if button_A.value:

pixels.fill(CYAN)

elif button_B.value:

pixels.fill(YELLOW)

else:

pixels.fill(LIGHTSOUT)

time.sleep(0.01)Press SAVE to run it, and play with the buttons.

You’ve also got a slide switch on there, which means you can add two more button-activated things. Let’s change between sound and color. We’ll need to add our audio back in again, and I’m also going to add a little bunch of notes to the setup to make things easier. Here’s the full code, with the new slide switch in the setup, the new notes, and our audio:

import time

import board

import neopixel

import digitalio

import simpleio

pixels = neopixel.NeoPixel(board.NEOPIXEL, 10, brightness=0.3)

digitalio.DigitalInOut(board.SPEAKER_ENABLE)

button_A = digitalio.DigitalInOut(board.BUTTON_A)

button_A.switch_to_input(pull=digitalio.Pull.DOWN)

button_B = digitalio.DigitalInOut(board.BUTTON_B)

button_B.switch_to_input(pull=digitalio.Pull.DOWN)

switch = digitalio.DigitalInOut(board.SLIDE_SWITCH)

switch.direction = digitalio.Direction.INPUT

switch.pull = digitalio.Pull.UP

#Colors

RED = (255, 0, 0)

YELLOW = (255, 255, 0)

GREEN = (0, 255, 0)

CYAN = (0, 255, 255)

BLUE = (0, 0, 255)

MAGENTA = (255, 0, 255)

WHITE = (255, 255, 255)

LIGHTSOUT = (0, 0, 0)

#Notes

C = 262

D = 294

E = 330

F = 349

G = 392

A = 440

B = 494

while True:

if switch.value:

if button_A.value:

pixels.fill(CYAN)

elif button_B.value:

pixels.fill(YELLOW)

else:

pixels.fill(LIGHTSOUT)

else:

if button_A.value:

simpleio.tone(board.SPEAKER, C, 0.4)

elif button_B.value:

simpleio.tone(board.SPEAKER, D, 0.4)

else:

pass

time.sleep(0.01)Paste that code in and press SAVE to run it. When the slide switch is on one side, the buttons make lights. When it’s on the other, the buttons make sounds! You can change the sounds or colors to whatever you like.

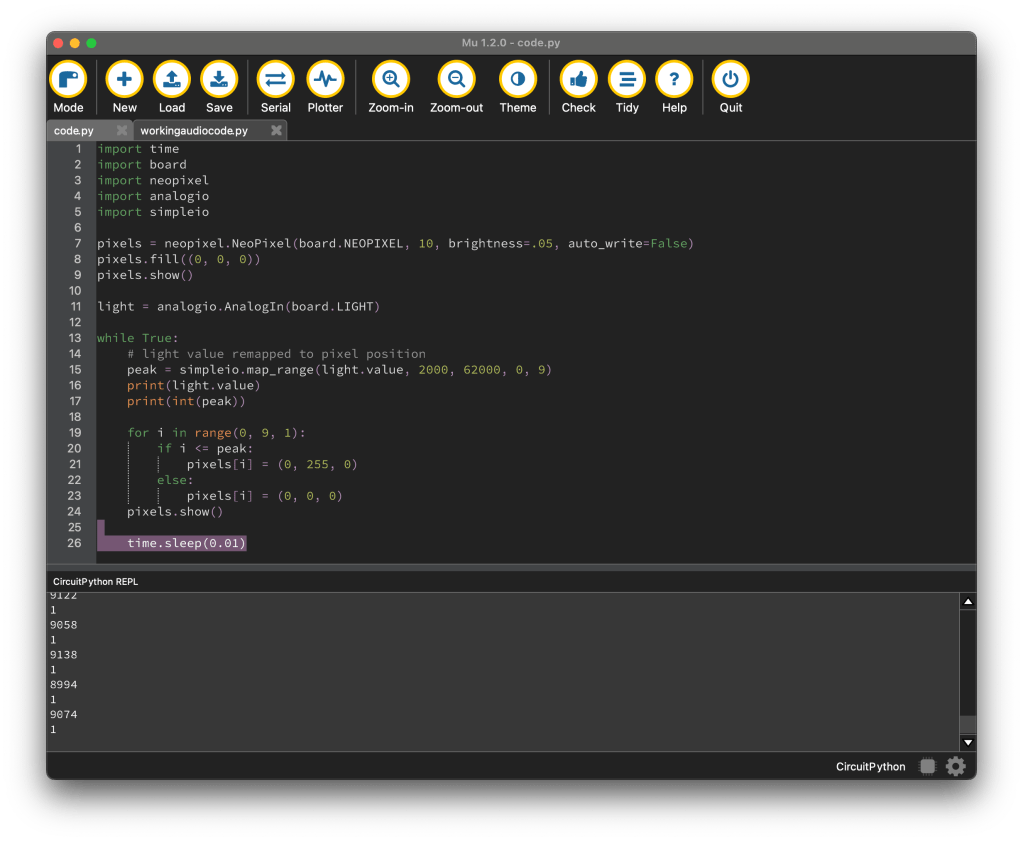

But this can definitely do more – in fact, it has the ability to respond to things like temperature, sound, and light. Let’s try a light sensor first. This code (which is an unmodified Adafruit example) will take in light and use the value to change the NeoPIxels- the brighter the light in the room, the more NeoPixels it lights up.

import time

import board

import neopixel

import analogio

import simpleio

pixels = neopixel.NeoPixel(board.NEOPIXEL, 10, brightness=.05, auto_write=False)

pixels.fill((0, 0, 0))

pixels.show()

light = analogio.AnalogIn(board.LIGHT)

while True:

# light value remapped to pixel position

peak = simpleio.map_range(light.value, 2000, 62000, 0, 9)

print(light.value)

print(int(peak))

for i in range(0, 9, 1):

if i <= peak:

pixels[i] = (0, 255, 0)

else:

pixels[i] = (0, 0, 0)

pixels.show()

time.sleep(0.01)Use the flashlight on your phone to see the lights go all the way up.

There’s a lot going on here – what’s most important, though, is this line:

light = analogio.AnalogIn(board.LIGHT)That creates the variable light, and sets it to be the value measured by the onboard light sensor – a value that comes in as an analog value and is stored as an integer (regular number). The rest of the code is using math to turn that number into a value that make sense for the NeoPixels. But what if we wanted to just see the value itself? We can – using something called the SERIAL. This is a way for our computer to read values straight from the CPX. See this line?

print(light.value)That line is printing the value from the light sensor to the serial port. To view it, go to Mu and click the button at the top that says SERIAL. You’ll get a new split screen labelled CircuitPython REPL and a stream of numbers immediately!

It’s got two alternating values- the raw light value, which is a large number, and the peak, which is the value it’s using to determine what Neopixel to turn on. Put a bright light near the CPX and you’ll see the peak number go up.

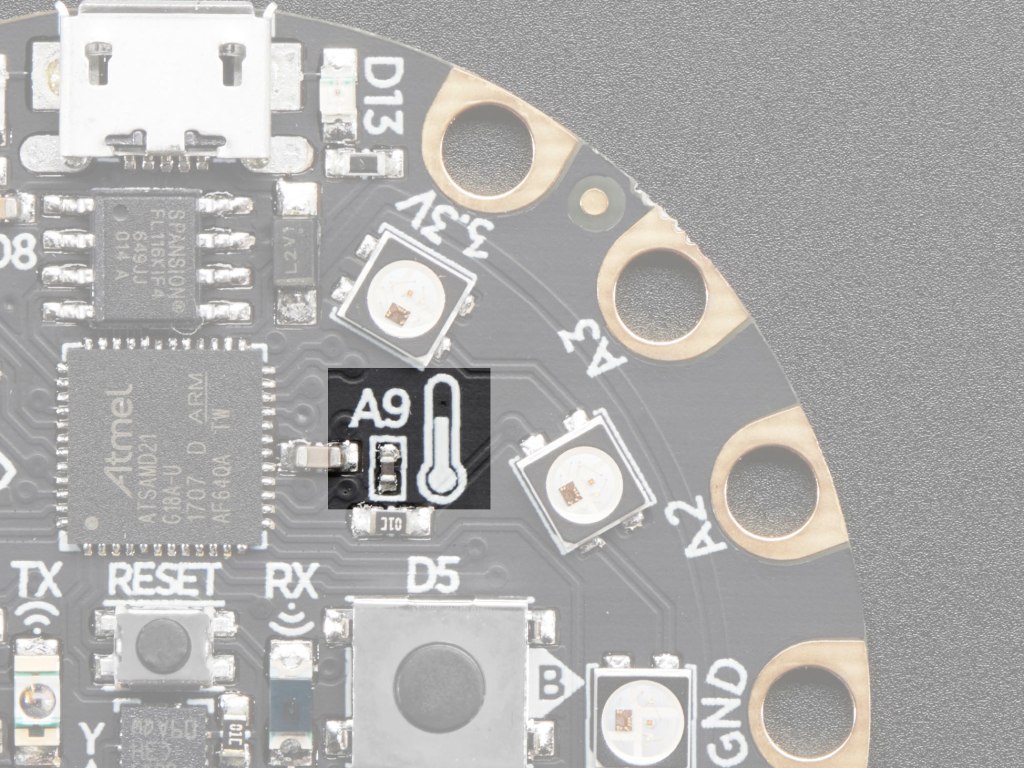

Let’s use our new Serial window to measure temperature using the CPX onboard thermometer. Clear the code and replace it with this unmodified Adafruit example.

Click SAVE and run the code, and your Serial output will change. Put your finger on top of the thermometer on the board – it’s in the upper right quadrant – to see a temp change (image credit Adafruit):

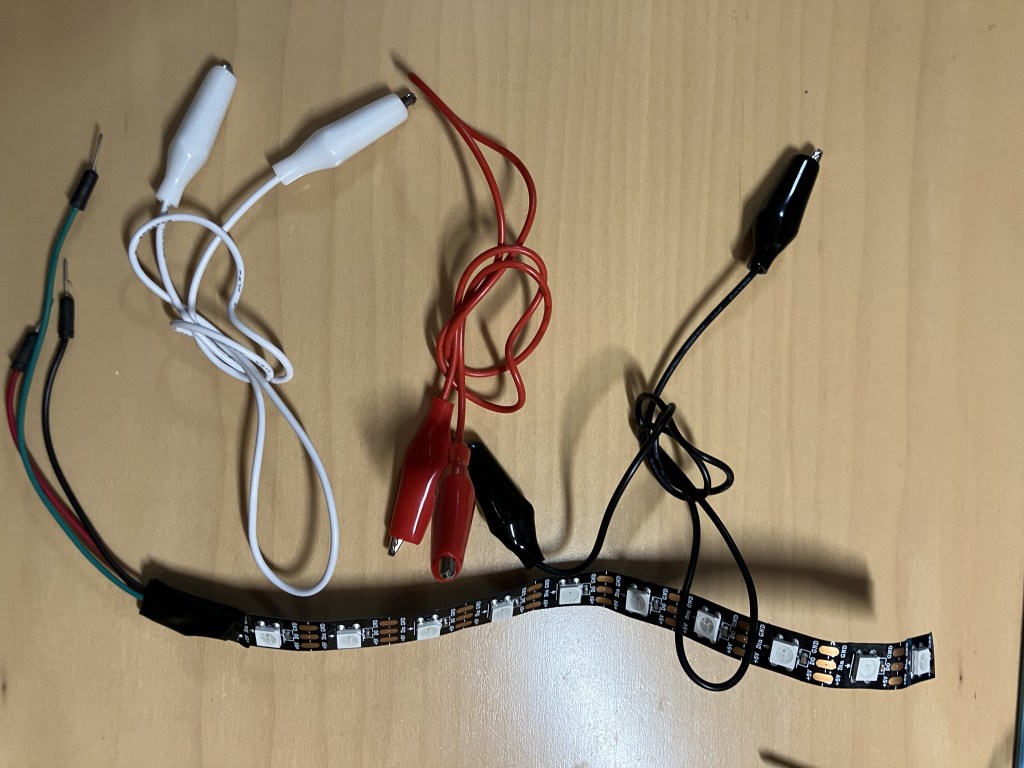

Ok, last one. This is a lot more complex. We’re going to use the onboard microphone to take sound samples and make a little audio meter. We can use the onboard NeoPixels for this, as the original Adafruit example does, but we’re also going to return to our first day of class and wire some stuff up. Grab these items from your kit:

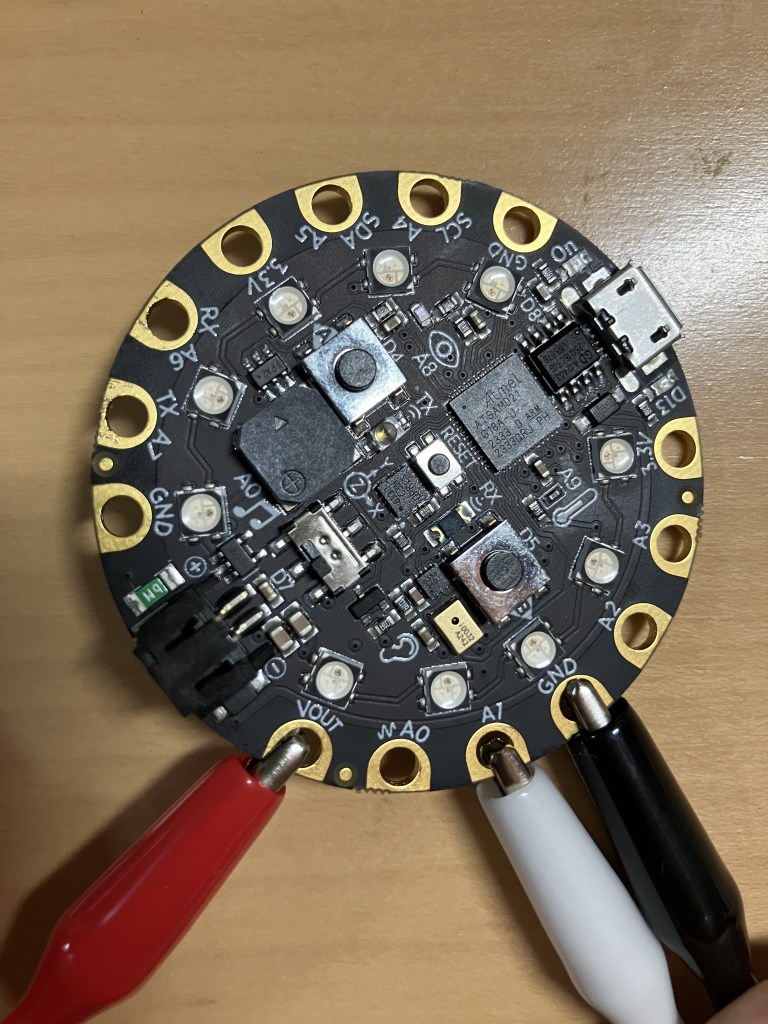

Your three alligator clips (you can use any color but to make things easier I’d recommend these three) and the strip of LEDs with trailing jumper wires. The LED strip has three outputs, the same as the original one we used with the GEMMA: Power (+5v), GND (-), and data (the down arrow). I’ve soldered jumper wires on to these to make your life easier- they should be red/black/another color to correspond to power/ground/data, but double check, then clip on the alligator clips (I’m once again using red for power, black for ground, and white for data)

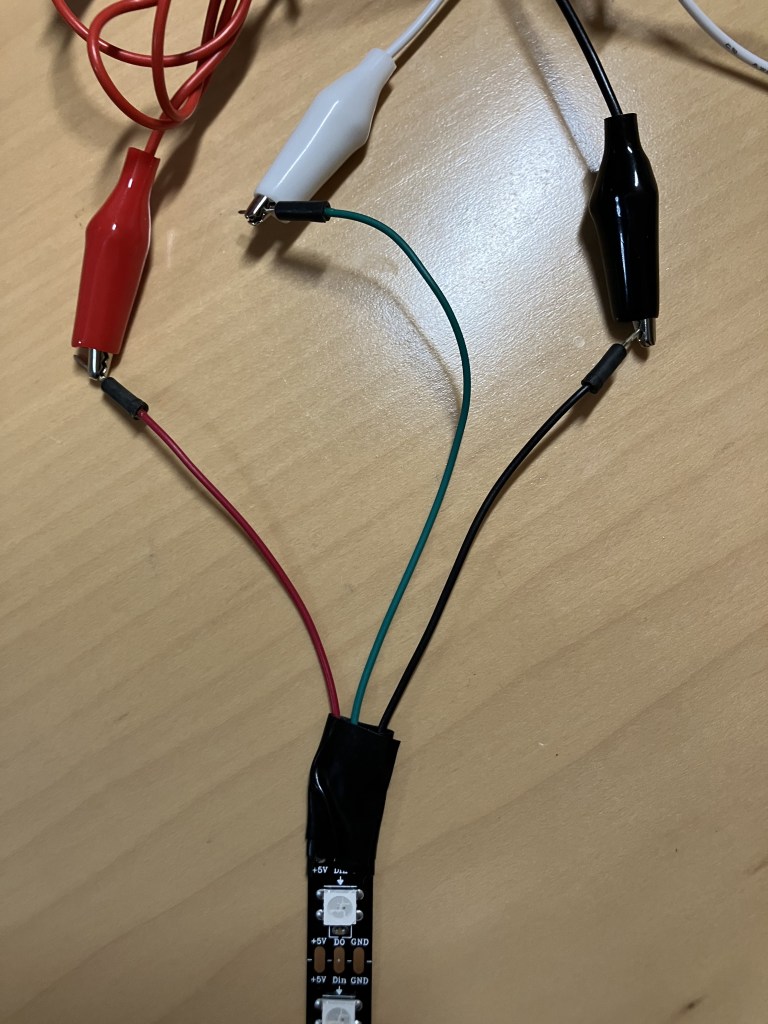

Then clip the other end of the alligator clips to your CPX – it works the same as the GEMMA! Red/power goes to the VOUT pad, white/data to the A1 pad, and black/ground to the GND pad:

Ok, now finally- go to the Mu editor, delete your code, and load this instead:

import array

import math

import audiobusio

import board

import neopixel

# Color of the peak pixel.

PEAK_COLOR = (100, 0, 255)

# Number of total pixels - 10 build into Circuit Playground

NUM_PIXELS = 10

# Exponential scaling factor.

# Should probably be in range -10 .. 10 to be reasonable.

CURVE = 2

SCALE_EXPONENT = math.pow(10, CURVE * -0.1)

# Number of samples to read at once.

NUM_SAMPLES = 160

# Restrict value to be between floor and ceiling.

def constrain(value, floor, ceiling):

return max(floor, min(value, ceiling))

# Scale input_value between output_min and output_max, exponentially.

def log_scale(input_value, input_min, input_max, output_min, output_max):

normalized_input_value = (input_value - input_min) / \

(input_max - input_min)

return output_min + \

math.pow(normalized_input_value, SCALE_EXPONENT) \

* (output_max - output_min)

# Remove DC bias before computing RMS.

def normalized_rms(values):

minbuf = int(mean(values))

samples_sum = sum(

float(sample - minbuf) * (sample - minbuf)

for sample in values

)

return math.sqrt(samples_sum / len(values))

def mean(values):

return sum(values) / len(values)

def volume_color(volume):

return 200, volume * (255 // NUM_PIXELS), 0

# Main program

# Set up NeoPixels and turn them all off.

pixels = neopixel.NeoPixel(board.A1, NUM_PIXELS, brightness=0.1, auto_write=False)

pixels.fill(0)

pixels.show()

mic = audiobusio.PDMIn(board.MICROPHONE_CLOCK, board.MICROPHONE_DATA,

sample_rate=16000, bit_depth=16)

# Record an initial sample to calibrate. Assume it's quiet when we start.

samples = array.array('H', [0] * NUM_SAMPLES)

mic.record(samples, len(samples))

# Set lowest level to expect, plus a little.

input_floor = normalized_rms(samples) + 10

# OR: used a fixed floor

# input_floor = 50

# You might want to print the input_floor to help adjust other values.

# print(input_floor)

# Corresponds to sensitivity: lower means more pixels light up with lower sound

# Adjust this as you see fit.

input_ceiling = input_floor + 500

peak = 0

while True:

mic.record(samples, len(samples))

magnitude = normalized_rms(samples)

# You might want to print this to see the values.

# print(magnitude)

# Compute scaled logarithmic reading in the range 0 to NUM_PIXELS

c = log_scale(constrain(magnitude, input_floor, input_ceiling),

input_floor, input_ceiling, 0, NUM_PIXELS)

# Light up pixels that are below the scaled and interpolated magnitude.

pixels.fill(0)

for i in range(NUM_PIXELS):

if i < c:

pixels[i] = volume_color(i)

# Light up the peak pixel and animate it slowly dropping.

if c >= peak:

peak = min(c, NUM_PIXELS - 1)

elif peak > 0:

peak = peak - 1

if peak > 0:

pixels[int(peak)] = PEAK_COLOR

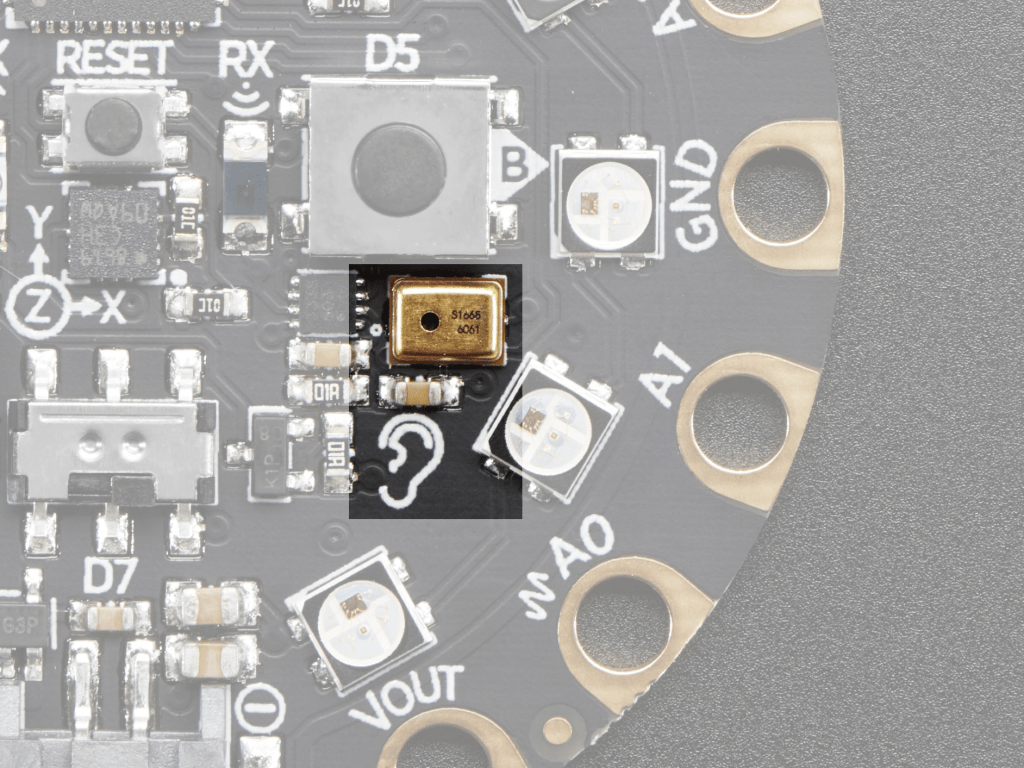

pixels.show()Click SAVE to run it, and boom, an audio meter. Snap your fingers over the board or talk into the microphone to see it work. Here’s the mic, if you have trouble finding it:

And that concludes the tour of sensors. Next week, you’ll be working on your own interactive object.